During the last years some books were published that allow the interested reader to follow track of Russia’s Imperial jewellery. Before that, one could read something here and there about beautiful jewels that had disappeared, but it was impossible to follow through and get the full picture. To many pieces, too few pictures, too little emphasis on giving sources and too little detailed recherche. Due to the collection being broken up and jewels being sold and scattered in all directions this might seem normal, but still it was unworthy of a treasure like this. Even today you can easily distinguish which Royal House in Europe has had Russian relatives – if there are really big tiaras and diadems on the ladies’ heads, you can bet on a Russian connection. The noble house of Luxembourg is a very good example.

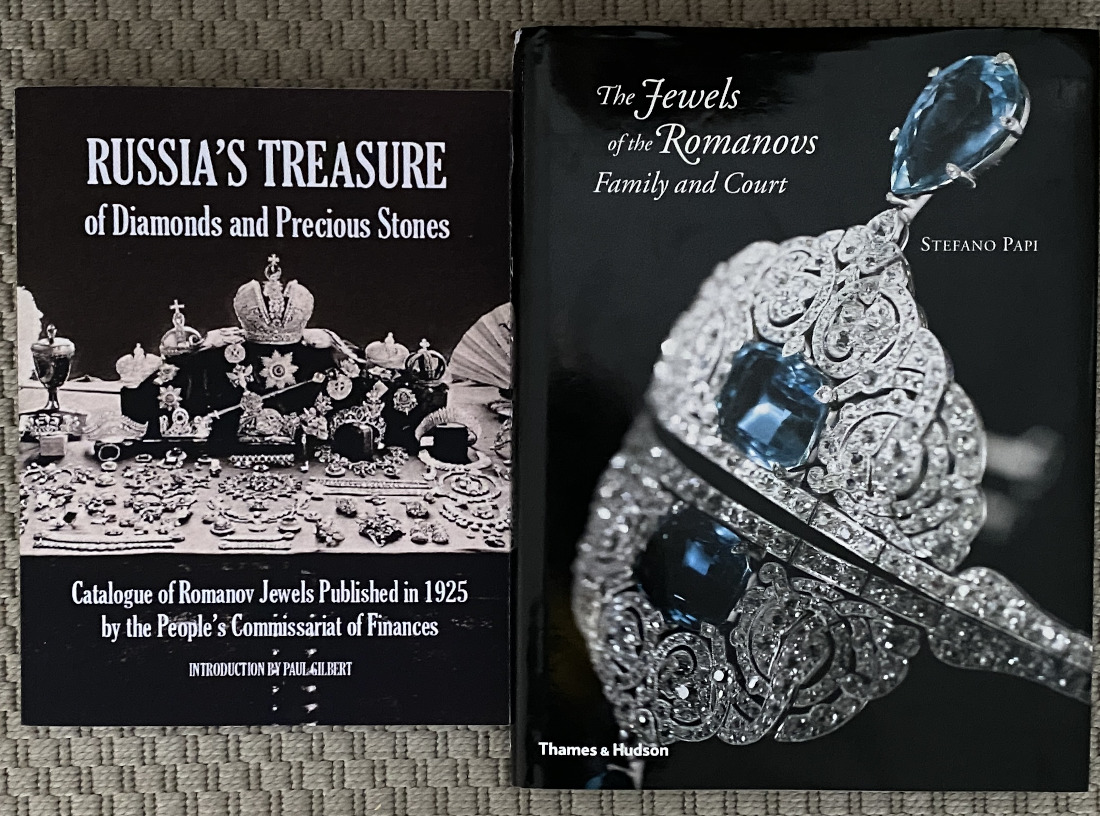

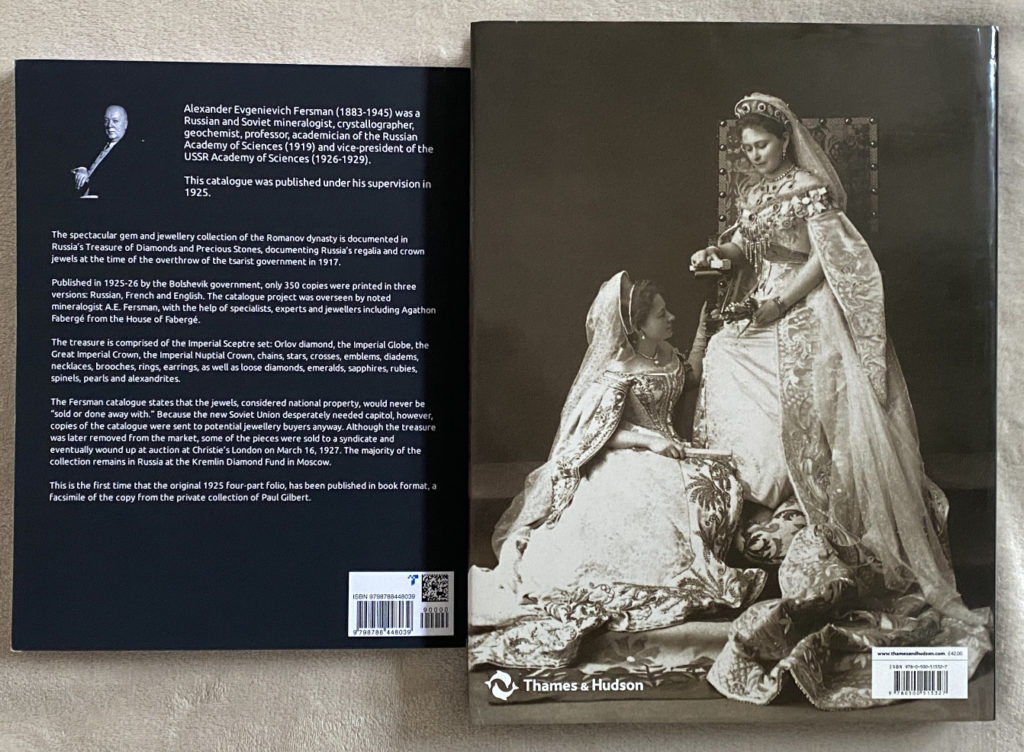

The facsimile reprint of the famous “Fersman catalogue”, through the initiative of Paul Gilbert, who has one of the original catalogues in his possession, is a milestone for anybody who is fascinated by the Romanov jewels. To have the full original catalogue available, with its descriptions and pictures, is wonderful. Alexander Fersman was a highly accomplished Soviet-Russian mineralogist and professor at the Academy of Sciences. The catalogue made under his supervision in 1925 is the most complete inventory of the older and newer Russian Crown Jewels. In 1927, a part of the jewels was sold at an infamous auction by Christie’s in London.

Another huge step towards the accountability of the collection is Natalya Semyonova and Nicolas Iljine’s book “Selling Russia’s Treasures”. They follow every piece of jewellery from the Fersman catalogue and next to a picture of each piece its whereabouts are stated. Seeing that list and the few pieces that are accounted for, one wonders what happened to the rest. Probably split up and sold in pieces of large diamonds, and the gold and platin melted down. How many of the diamonds and precious stones might have been stolen by the people who handled them? No one will ever know.

“Selling Russia’s Treasures” does much more than follow only the jewellery; it tracks paintings and furniture and all other kinds of art. Everything that was transferred in the early 1920s to the so called “State Valuables Depository – Gokhran”. Gokhran organized the Christie’s sale in 1927. It is an incredible valuable book and a sad testimonial to the actions of the state in a phase of turmoil, where quick cash was king. Today’s assessment of the sales success is sobering – it made no real difference to the state finances. I did not include a picture of the book in the article, as is front and back cover does not show jewellery.

The third book used here is Stefano Papi’s “The Jewels of the Romanovs, Family and Court”. Its beauty lies in the many colourful pictures of the jewels and the many stories of Romanov family members and their heirs about the jewels. This book brings back the glamour and the tragedy of the jewels’ owners.

What was left of the sumptuous crown jewels, is today on display in the Kremlin’s Armoury. I was very lucky to visit it once, on the intuition of a moment. Going inside the Kremlin was never something made easy for anybody. I was first struggling with the not very friendly Russian-only speaking ticket sales ladies and later, inside the huge Kremlin court without written directions that I could read, first taking the wrong entrance, and being chased out by police or soldiers. It might have been the year 2016. There were not many visitors, neither foreign nor Russian. The Armoury was stupendous, yet not too big. The important matter is that one can (was able) to go there and look at the Romanov jewels and almost touch them behind the thick glass on their purple velvet background sheets. The visit passed in a blur; it was sensational just being there.

The Imperial Crown had the central place in the exhibition, as it was the most famous of them all. Even Catherine the Great had worn it. Same goes for the sceptre with the Orlov diamond. There were many diamond chains with eagles. Those highly important historic jewels had not been destroyed, but kept by the Soviets.

The Russian authorities had taken the effort to recreate some of the jewels that had been destroyed or disappeared. The most beautiful diadem of them all, made by court jeweller Bolin for Empress Alexandra and worn by her only once in public, in 1906, was one of them. It features diamonds and pearls. One row of small pearls at the base, in the middle dangling pearls and at the top of the diadem a row of big pearls. All held together by a huge and still playful diamond platinum structure. There are a few diadems around in Great Britain and other countries that also feature pearls, but usually only one row, either standing up or dangling, between a structure of diamonds. Princess Diana liked to wear one, as did Queen Elizabeth II. But all those were small. Empress Alexandra’s is in a different league. It is seriously big; the whole thing is at least 15 cm high and the most beautiful tiara I know.

If you google “Empress Alexandra’s pearl and diamond diadem” you can see it (or look it up in Stefano Papi’s book on page 56/57). Unfortunately, the tiara is not in the Fersman catalogue cover pictures above, it was placed a little more to the left on the table in the original photograph.

The never smiling Empress wore her diadem with dignity. Her case shows best that great wealth does not guarantee a happy life. Hers and Emperor Nicholas II marriage was a love match, but it seems they were not liked by many around them even long before the revolution. The surviving pictures of her seem to precede her tragic fate. Some people are simply not born for the position life has dealt them. Power, wealth, and fame can bring you on your knees, as any powerful weapon can turn against its inexperienced handler.

This diadem did disappear after the Fersman catalogue was published. There is no trace of what happened to this wonderful piece. The Russians recreated it for the exhibition. You can see that easily on the pearls. They are all round and flawless. The original ones were natural/oriental pearls of the highest quality, but not perfectly shaped. Same goes for some of the other diadems sold in London in 1927, all were recreated more perfect than the originals and can be seen in the Armoury.

In Russia the contrast between rich and poor has always been stark. It must have been much worse 200 years ago than today, but even today the billionaires and powerful politicians act different from most of their counterparts in the West. No one knows how much blood, tragedy, and pain it caused the Russian peasants to pay for all the jewels the Russian Emperors and noble families amassed. Somewhere the money must have come from. Jewellery does not age, does not show pain, does not diminish over the years. Through the never smiling last Empress some much needed gravity is given to the lost and recreated treasures of the Russian crown.

All rights to the books belong to:

Russia’s Treasure of Diamonds and Precious Stones, Catalogue of Romanov Jewels Published in 1925 by the People’s Commissariat of Finances, Facsimile-Reprint made possible by Paul Gilbert, 2022, ISBN: 979-8-788448-03-9

Semyonova, Natalya and Iljine, Nicolas V.: Selling Russia’s Treasures, The Soviet Trade in Nationalized Art, 2013, published by The M.T. Abraham Centre for the Visual Arts Foundation, 21 Boulevard Haussmann, 75009 Paris, France, Printed and Bound in China, ISBN: 978-0-7892-1154-5

Papi, Stefano: The Jewels of the Romanovs, Family and Court, 2010, Published by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181 A High Holborn, London, WC1V 7QX, Printed and Bound in China, ISBN: 978-0-500-51532-7